Uncategorized

Seneca College’s ‘baseball guy’ joins Order of Canada

Published

3 years agoon

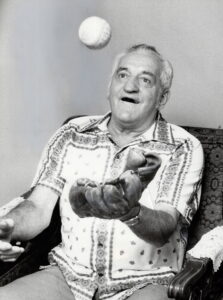

Bill Humber credits Seneca for his achievement

Jan. 20, 2022

He may have retired from Seneca in 2018, but Bill Humber is going into extra innings as Canada’s premier baseball historian.

Mr. Humber has been appointed a member of the Order of Canada for his contributions highlighting Canadian baseball history. The Order of Canada is one of the highest civilian honours in the country, recognizing “outstanding achievement, dedication to the community and service to the nation.”

Mr. Humber’s appointment to the order was among the 135 announced in December 2021 by Gov. Gen. Mary Simon.

“I’ve come to realize that baseball may have been the context for this honour, but it’s like a lifetime achievement award,” Mr. Humber said. “It’s a recognition for my academic work and sharing that knowledge with others. And I give a lot of credit to Seneca for the work I did.”

Mr. Humber joined Seneca in 1977 and served as program co-ordinator, chair and director during his 42-year career. He created the popular Baseball Spring Training course in 1979 to offer fans opportunities to discuss the upcoming season in a classroom setting and learn about baseball from broader historical, cultural and business contexts.

He published his first book, Cheering for the Home Team, in 1983. Eleven more books followed, including Let’s Play Ball: Inside the Perfect Game (1989), The Baseball Book and Trophy (1993) and Diamonds of the North: A Concise History of Baseball in Canada (1995).

In 2018, Mr. Humber became the first academic researcher to be inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame.

Bill Humber has published 12 books, many of them about baseball. His 13th book, about soccer, is coming out this spring.

While he is widely known as a baseball expert, Mr. Humber is also an environmental educator who developed and fostered academic programs in environmental restoration, building environmental systems and energy management.

He is the founding director of the Office of Eco-Seneca, creator of Seneca’s Green Citizen initiative and a member and past co-chair of the Sustainable Seneca Committee.

Mr. Humber’s commitment to the environment earned him a national award for educational leadership in sustainability from the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation in 2012. In 2019, he won bronze in the Colleges and Institutes Canada’s Leadership Excellence Award for Managerial Staff.

“All of the different things I have done, I cherish them all,” he said. “And I hope to do more in the future.”

Mr. Humber’s latest book, coming out this spring, is about soccer as a mainstream sport in North America. It is a collaboration with his eldest son, Brad, a Seneca broadcasting graduate and Sportsnet producer, and includes a chapter about the Seneca Sting women’s soccer team.

Previously, Mr. Humber collaborated with his younger son, Darryl, on Let it Snow: Keeping Canada’s Winter Sports Alive (2009).

“The joke in the family is when am I going to do a book with my daughter, Karen, who works in the Faculty of Applied Science & Engineering Technology at Seneca,” he said.

Joking aside, Mr. Humber says he hopes people will remember both the baseball and environmental sides of his career.

“But I know after I’m gone, people are going to talk about me as the baseball guy in my obituary,” he said. “I’m fated to be the baseball guy.”

You may like

-

NorthPaws get a timely hit in the seventh to complete the comaback against the AppleSox

-

NightOwls Wings Get Clipped In An Exhibition Game Against The Nanaimo Selects

-

Victoria HarbourCats – Dudes hold on for narrow win on Fireworks night

-

Bring out the Brooms as the Nanaimo Bars Sweep The RiverHawks

-

Victoria HarbourCats – Sox hang on to complete sweep of Cats

-

Despite out hitting the Bells the NorthPaws could only manufacture one run

Uncategorized

Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame hosts virtual induction ceremony

Published

4 years agoon

November 15, 2021

By Ryan Drury CKNX NEWS TODAY

The Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in St. Marys hosted a virtual induction and awards ceremony on November 16th.

The Hall celebrated the class of 2021, which consists of 16 individuals and one team. Along with the induction ceremony, the winners of the 2019 and 2020 Jack Graney Award, handed out annually for media excellence, and the James Tip O’Neill Award, which is presented to the top Canadian player each year, were honoured. The class of 2021 includes the induction of the 1877 London Tecumsehs, the International Association championship-winning team from London, Ontario.

The 16 individual inductees, all of whom are deceased, and one team were selected by a six-person Committee comprised of Canadian baseball historians from across the country.

“We are excited and proud to celebrate such an important and diverse group of trailblazers and pioneers of Canadian baseball,” says Jeremy Diamond, the chair of the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame’s board of directors. “Their induction will ensure that the profound impact they have had on baseball in our country will live on and be shared in our museum for future generations.”

The 2021 inductees are:

Bob Addy, player, Port Hope, Ont.

James F. Cairns, executive, Lawrenceville, Que.

Helen Callaghan, player, Vancouver, B.C.

Jimmy Claxton, player, Wellington, B.C.

Charlie Culver, player and manager, Buffalo, N.Y.

William Galloway, player, Buffalo, N.Y.

Roland Gladu, player and scout, Montreal, Que.

Vern Handrahan, player, Charlottetown, P.E.I.

Manny McIntyre, player, Devon, N.B.

Joe Page, executive, London, England

Ernie Quigley, umpire, Newcastle, N.B.

Hector Racine, executive, La Prairie, Que.

Jimmy Rattlesnake, player, Hobbema (Maskwacis), Alta.

Jean-Pierre Roy, player and broadcaster, Montreal, Que.

Fred Thomas, player, Windsor, Ont.

Roy Yamamura, player and executive, Vancouver, B.C.

1877 London Tecumsehs, International Association championship-winning team, London, Ont.

The Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame’s class of 2020, which consists of former players Justin Morneau (New Westminster, B.C.), Duane Ward, John Olerud and legendary Montreal Expos broadcaster Jacques Doucet, will be inducted separately in an in-person ceremony in St. Marys on June 18th, 2022.

Jack Graney Award winners

2019 – Ken Fidlin, Toronto Sun

After beginning his journalism career with the Woodstock Sentinel Review, Fidlin enjoyed tenures as a sportswriter with the Kingston Whig-Standard, Ottawa Journal and Ottawa Today before being hired by the Toronto Sun in 1980. He proceeded to become a highly respected Blue Jays beat writer and columnist until he retired in 2016. In all, he spent 45 years as a sportswriter and had the opportunity to cover 20 World Series, two Stanley Cup championships, two Olympic Games, five Super Bowls and nine Grey Cups.

2020 – Dan Shulman, Blue Jays TV play-by-play commentator, Rogers Sportsnet

Shulman began his professional broadcasting career with CKBB, a Barrie, Ont., radio station, in 1990 and in 1991 he moved on to the FAN 1430 (now Sportsnet 590 The FAN). In 1995, he began serving as the Blue Jays’ play-by-play commentator on TSN and also worked part-time for ESPN. He joined ESPN full-time in 2001 and was the voice of Wednesday Night Baseball from 2002 to 2007, Monday Night Baseball from 2008 to 2010 and Sunday Night Baseball from 2011 to 2017. The Toronto native has now been calling MLB postseason games on the radio for ESPN since 1998 and World Series contests since 2011. Shulman returned to the Blue Jays TV crew in 2016 and has been calling games for Rogers Sportsnet.

James “Tip” O’Neill Award winners

2019 – Mike Soroka, Atlanta Braves

In 2019, his first full major league season, Soroka posted a 13-4 record and a 2.68 ERA, while striking out 142 batters in 174-2/3 innings in 29 starts for the Braves. For his efforts, the Calgary, Alta., native was named to the National League All-Star team and a starting pitcher on Baseball America’s MLB All-Rookie team.

2020 – Jamie Romak, SSG Landers

In 2020, Romak batted .282 with 32 home runs in 139 games for the SK Wyverns (now SSG Landers) of the Korean Baseball Organization (KBO). On top of his power numbers, the London, Ont., native also had 85 runs, recorded 32 doubles and walked 91 times, while registering a .546 slugging percentage and a .945 on-base plus slugging percentage (OPS).

Uncategorized

A sure bet – how one family gambled on Victoria, and baseball — and won

Published

4 years agoon

November 3, 2021

VICTORIA, B.C. — “Mom, what’s the count?”

The question, flatly posed, came from a knowledge of the game, from an intent focus that would match the character played by Clint Eastwood in Trouble With the Curve, but certainly the opposite end of the age spectrum. This was a Baseball IQ conversation.

It was asked in a fresh new baseball setting in the Stadium District of B.C.’s capital city, in the Edwards Family Training Centre that houses the Victoria HarbourCats players club. The lounge area of the former squash court complex now transformed into turf floor and netting galore, had about eight people in it, watching the Tampa Bay Rays play the Toronto Blue Jays, the game in late innings and the outcome hanging on every pitch.

“1-and-2, Cian.”

That’s Cian, as in Cian (pronounced Key-an) Carter. Whose lifespan is all but five years since he was born to Adrienne, mom in this case, and father Ryan Carter.

Cian and his family are a very interesting story, as complex and yet as normal — and as intriguing — as they come. Baseball, poker, family, even Lego and Star Wars, and how they settled on living in Canada, and Victoria, returns to baseball, always.

THE FLOP

The Carter parents were not born and raised in Victoria, as many wish they had been. Adrienne is from Edmonton, a former Occupational Therapist lured away by a Texas Hold Em talent. Ryan is from Detroit — college wasn’t for him, but the Vegas poker tables sure were. They met in Vegas through a mutual friend, but found their best earnings in online tournaments. And, because it always comes back to baseball, they love the Tampa Bay Rays nearly as much as they love their own children.

Yet their story of arriving, and staying, in Victoria, is about Cian, and his sandwich siblings Carrick, 7 and Caitlin, 3. They’ve been in Victoria for two years, and the roots have taken, not because of poker, or their extended families being nearby.

Why Victoria?

Baseball. That’s it. Baseball. A Canadian city, selected for climate, for location, for size and programs, and all because of how it spokes back to the hub of their family, which is a love of baseball.

“We choose to live our life around our vision and our loves, and we love baseball,” said Adrienne.

Carrick is part of the Beacon Hill Little League program, and never misses a session at the HarbourCats Players Club at the Edwards Family Training Centre. His siblings, home-schooled by Adrienne and Ryan, can’t wait to join him. In fact, now all three kids are registered with Beacon Hill LL and both Carrick and Cian are in the Players Club now — with Ryan now helping as a coach, and Adrienne pulling double duty as registrar and coach.

“Carrick is very good at math,” says Ryan, “and has learned the majority of his math through baseball. Baseball is used as a reference in a lot of their learning. We’ve been looking for a house, and one of the main considerations is about access to a park, about how it relates to baseball and the kids.”

Carrick attended his first baseball instructional camp at age 3. He wouldn’t take no for an answer when the camp nearly declined his participation — the next oldest kid was 10. He played t-ball as a 4-year-old when the family spent a summer on Long Island, NY, and then followed up there with a second summer.

“Why Victoria?” repeated Adrienne. “We analyzed like poker players, made charts — turn and river. We were in Peachland (just south of Kelowna, B.C.) for seven years, then moved to Victoria — we vacationed here, loved the climate, that you can be on the fields year-round. Carrick was one of the first to sign up with the new HarbourCats Players Club. We went to West Coast League games in Kelowna, and a Victoria HarbourCats player gave Carrick a ball, that stuck with us.”

THE TURN

The three kids were all born in the Okanagan. Ryan and Adrienne have shifted away from poker — kind of. COVID has limited everyone’s ability to get involved these last 20 months, or the people of Victoria would know their new neighbours quite well. They’d have been at all HarbourCats games, and having the kids involved in every program possible.

But now, you see the three running around at games of the Victoria Golden Tide, the newborn entry in the Canadian College Baseball Conference. Carrick — if it’s possible to predict a future as a MLB manager at age seven, Carrick is THAT kid — is seen wearing a black and orange B hat for his fresh voyage with Beacon Hill Little League. The three have an imagination for the game that recalls days of old before PlayStation, before Jays in 30, even before slow motion replays — they’d have fit in the 1920s, playing stickball wherever they could find an open space.

“We were looking for childcare help, and we were very open about it — candidates had to love baseball, Lego and Star Wars, in that order,” said Adrienne. “And not just be ok with those things, you have to LOVE them. Or it won’t work, it’s that simple.”

Carrick and Cian are members of the HarbourCats Players Club, which provides foundational youth instruction based first and foremost on one enduring principle — fun. Structured, yes, tailored for each young player, yes, but the program leaders never lose sight of the fact you play baseball, you don’t work baseball.

“Carrick wears baseball pants every day, the only time isn’t wearing baseball pants is when we force him to put something else on,” said Ryan. “That’s just what he wears.

“Only Rawlings. His R pants, that’s what he calls them.”

THE RIVER

This is where the back story gets very, very interesting.

Adrienne and Ryan met in one of the most mentally-taxing atmospheres — a pair of aces in the world of professional poker. Ryan, now 37, has a couple of wins under his belt, including his biggest — $600,000-plus in an online tournament just weeks after taking on a new mindset coach (more on that shortly) . Adrienne found success as an elite mixed games player and a leader in the industry, representing how dynamic and accessible poker could be to players all over the world.

Ryan was raised in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and attended the University of Michigan. He took up poker at 18. “But I haven’t played in about seven years, since Carrick was born — you have to play a lot to keep sharp, kinda like baseball,” he adds.

Online poker players will likely recognize the name Talonchick — that’s Adrienne, nee Rowsome, who did some live events but was mostly successful as a fully sponsored PokerStars pro.

THE RAYS

The one obvious question is their family choice in favourite MLB teams, but it makes complete sense when you apply the poker mentality. If you have the analytical mind to be successful as a poker player, no franchise would better mirror the poker psychology that has kept the small-budget Tampa Bay Rays fully competitive in the big-spending American League East.

Ryan grew up a Tigers fan, Adrienne would go to Trappers games with her dad, Paul, when the current ReMax Field in Edmonton was named for John Ducey, and you could smell the wood of the rafters, the oozing of baseball history.

Methodically, she picked her team while waiting for Carrick to arrive. What she wanted was an AL team, didn’t want a big budget team, and Joe Maddon was managing and doing things using poker-like statistics to gain advantages, to hedge his bets. He’d deploy seven infielders and two outfielders, willing to try things others weren’t doing, one-third of the budget of the Yankees. “They have never let me down — they hustle, they play hard,” said Adrienne.

Ryan bought in, too. They watch every game, planning family trips (pre-covid, of course) to see the Rays play live.

“You’re always either overperforming, or underperforming, with the value of your salary — future potential or past success, and the Rays are good at valuation and letting players be themselves,” said Ryan. “They find value where others don’t. They fit with our life goals and what we do, finding potential.”

Adrienne started in poker at 22, and played in the World Series of Poker at 24. Not unrelated, the side hustle turned into a house and a BMW by 25 — she loved her job as an Occupational Therapist, but didn’t like punching the clock. The couple met through a mutual friend, at the Rio in Vegas, in 2011, the same year she signed with PokerStars. She remained a sponsored pro until 2018.

What they do now is coach, and advise. Ryan’s success in the game inextricably coincided with working with Elliot Roe, a former Brit now based in Utah who used hypnosis to overcome a fear of flying and became enthralled with the untapped potential of the human mind. They have now combined on an app and company called Primed Mind, coaching mindsets and performance, and Ryan has developed programs directed toward, you guessed it, baseball.

It doesn’t stop there. Golfers, poker players, and top athletes are working with Primed Mind — including multiple medal-winning American Paralympian Nick Mayhugh, who set three world records in sprinting (T37, Cerebral Palsy) at the recent Tokyo Games.

“What started focusing on poker players has branched out to Wall Street, to top athletes, to anyone in high performance industries who feel they have hit a ceiling,” said Adrienne. Added Ryan — “We work with CEOs, athletes, crypto traders, MMA champions, and poker champions with more than $200 million in earnings.”

And with all that, Ryan’s face lights up more with a baseball note, than with all their collective success at the real or virtual tables. It comes from a recent Victoria Golden Tide game, the Canadian College Baseball Conference team in its inaugural fall session at Wilson’s Group Stadium in Victoria.

“I caught my very first foul ball last weekend,” he beamed. “All those games, never got one. That was awesome.”

Canadians in Pro Baseball

Moving Pictures – The Alpha Wolf of Baseball Films

Published

4 years agoon

March 23, 2021

Ani Kyd Wolf is a musician, film director and actor trying to turn a very special double play.

Wolf was on the production team for one of the most acclaimed baseball movies of the past three years. The Silent Natural hit several long-balls on the film festival circuit, as well as with the hearing challenged community. It was an official entry (one of only 10) in the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s 14th Annual Film Festival held at the Bullpen Theatre in Cooperstown. It stars Sheree J. Wilson (Walker, Texas Ranger), Sam Jones (Flash Gordon), Vernon Wells (Road Warrior), and deaf actor Miles Barbee in the lead role of William “Dummy” Hoy, the first deaf baseball star in history. Hoy played MLB centre field from 1888 to 1902 starting with the Washington Nationals and most notably for the Cincinnati Reds with whom he retired and is a member of their team Hall of Fame.

But perhaps Hoy’s most enduring legacy is seen at the end of every pitch when umpires gesture different ways for balls or strikes. It is believed he played a role in the development of these hand signals.

What doesn’t have to be believed, because the records are clear, is the way he played baseball. During his major league career he hit .288, got more than 2,000 hits, drove in 725 runs, and stole 596 bases. He once threw out three runners at home plate from centre field, unassisted, in a single game. At the age of 99, to a standing ovation he could see and surely feel but not hear, he threw out the first pitch of Game 3 at the 1961 World Series at Crosley Field in Cincinnati.

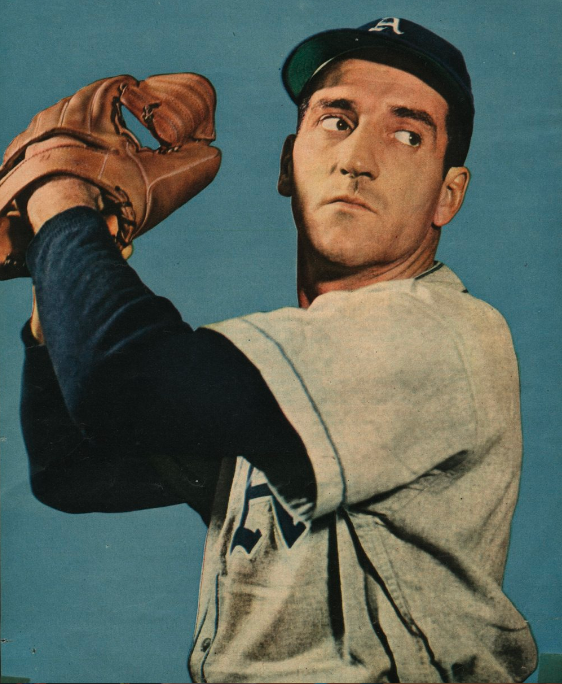

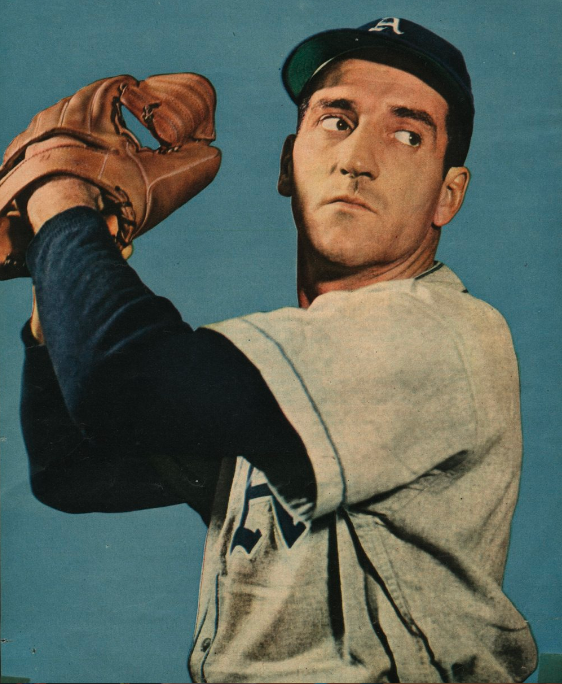

William “Dummy” Hoy

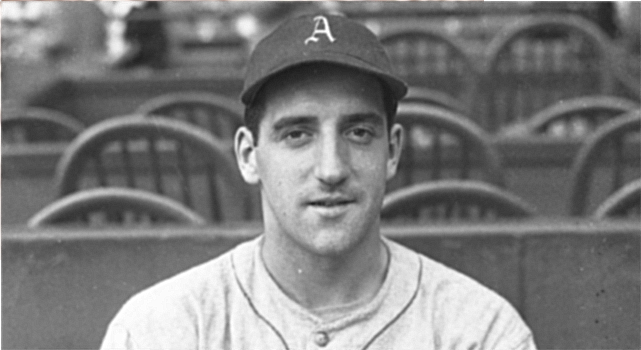

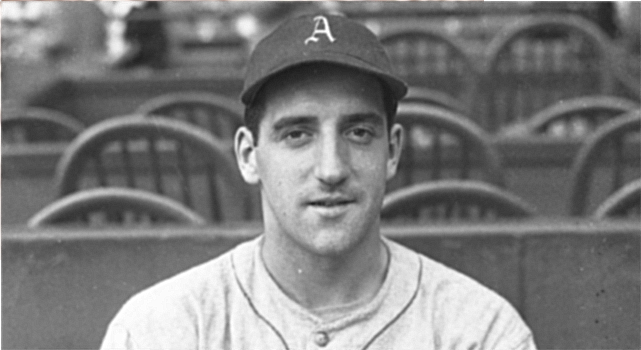

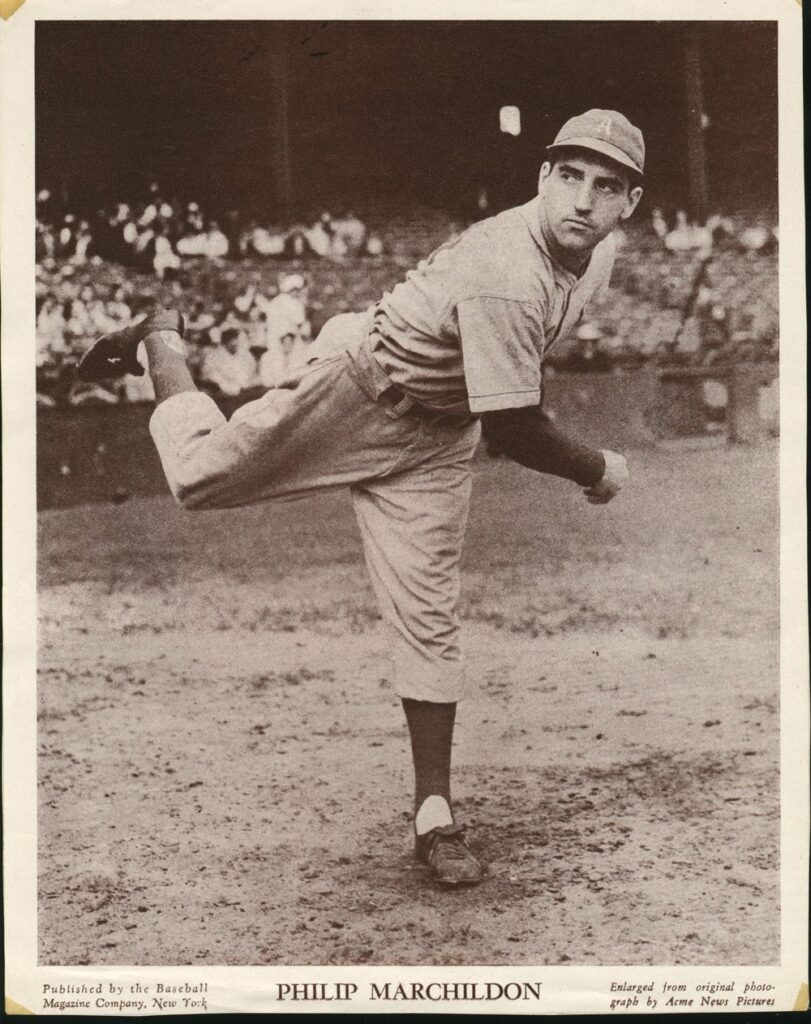

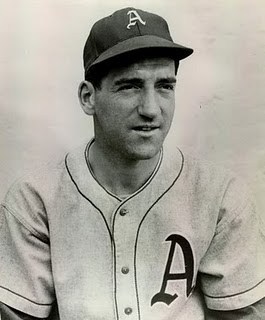

From that true diamond tale, Wolf is involved in the development of a second baseball biopic. This one depicts the life of ace pitcher Phil Marchildon whose top-of-the-rotation career with the Philadelphia Athletics was interrupted by only 1.1 innings pitched for the Boston Red Sox to end his career and three years hurling machine gun fire from the tail of a Halifax bomber high over Nazi-infested Europe.

Suffering from acute PTSD and the physical trauma of nine months in a hellish prisoner of war camp to close WW2, he came back to anchor the A’s pitching staff and finish with a career 3.93 earned run average and 481 strikeouts.

Marchildon was elected to the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in 1983, the first year of the organization’s existence. He was inducted into the Canadian Sports Hall of Fame in 1976.

That’s right, Marchildon was a hero of the Royal Canadian Air Force as well as major league baseball.

He was also a relative of Wolf’s, she being born in Hamilton, the daughter of folk singer Dianne Kyd. Her family is largely rooted in Ontario, although Wolf was raised in B.C. from the age of 10.

After the edifying experience of telling the Dummy Hoy story on film, Wolf was hooked on the sport’s unique ability to drive in a good human tale. She could think of none better than her own forbearer.

Ani Kyd Wolf

“I come from a baseball family,” said Wolf from her home in the hamlet of Hixon, located halfway between Prince George and Quesnel in northern British Columbia. “My younger brother Luke is really into it. He’s no major leaguer but he’s in his 40s and still just loves to play, and he said ‘you know, you’ve got to read about Phil Marchildon; he’s family.’ He is our grandmother’s first cousin. Luke kept telling me to read his story, so, ok, fine, I’ll read his story. And when I dove into his life, I was blown away. I was like ‘Can this be real? Is this actually real and a member of my family?’ It became immediately important to me to do a film about Phil.”

Wolf had grown up knowing of the major leaguer in their family tree. It wasn’t an obscure relative, either. Although he passed away in Toronto in 1997 before she could meet him, she knew his direct descendants in the generations closer to her own.

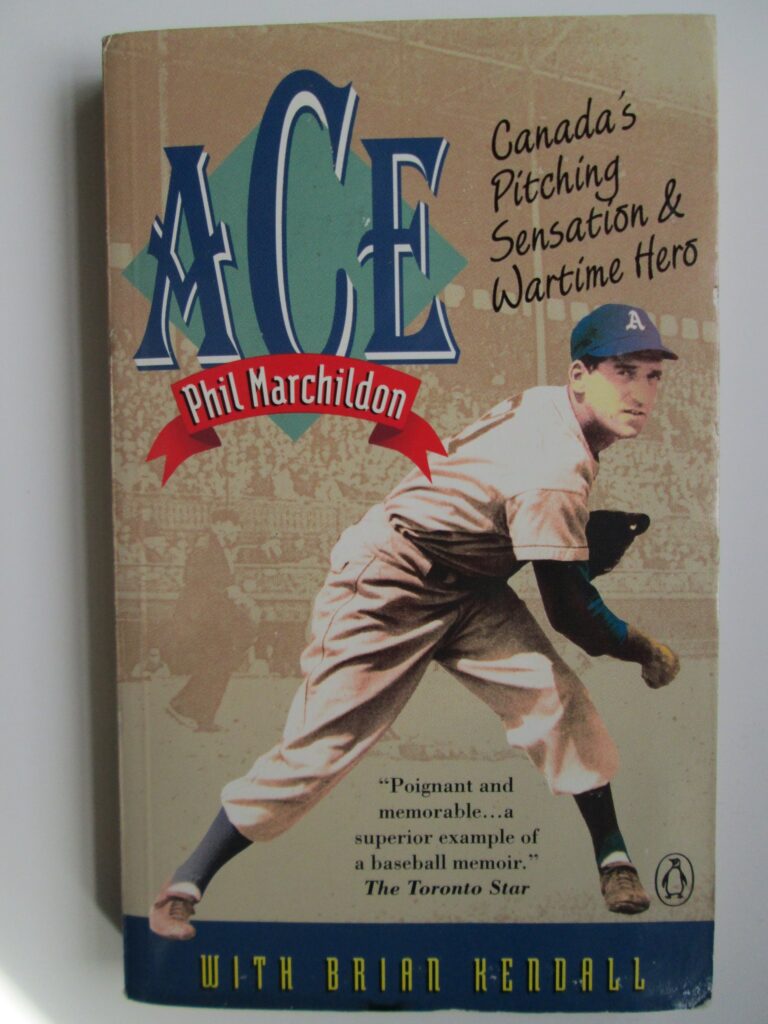

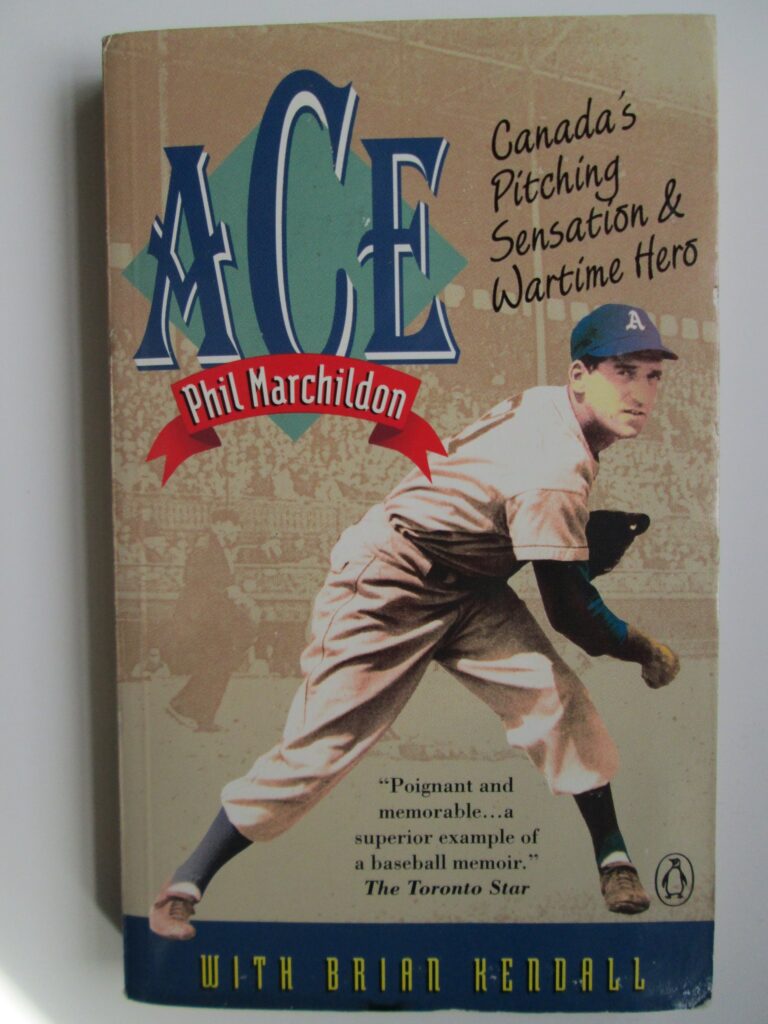

Until her brother pushed his biography into her hands – Ace: Phil Marchildon, Canada’s Pitching Sensation and Wartime Hero written by Brian Kendall – she did not grasp just how cinematic his life had been. Wolf admitted she had to look a bunch of facts up as she read the book because she just couldn’t believe it all happened to one person, but it was all verifiable.

“It is almost like a Forrest Gump story, where one guy goes from famous situation to famous situation, but he always considered himself just a kid from Penatang (the nickname of his small Ontario hometown of Penetanguishene),” said Wolf. “We don’t have to warp it for dramatic purposes, we just have to tell it like it happened. The real challenge is going to be what to leave out, because there is so much amazing material to this man’s life. That’s what we are going through right now. The way Heather has it set up in the script is quite beautifully woven.”

Heather Kyd is her aunt, who grew up knowing her cousin Phil. She is also an experienced writer. She has taken on the screenplay duties while Wolf is handling the directing and co-producing roles. Marchildon’s daughter Donna is helping flesh out the detailed truths of the story for them.

Marchildon was just a local ball player for his employer’s team, Creighton Mines, in the Nickel Belt League. He got a full-ride scholarship after high school for St. Michael’s College in Toronto but that was for football.

The pigskin career got fumbled, however, but at age 20 he was a standout pitcher for the Spencer Foundry Rangers back in his hometown and the following year was the ace of the Penetanguishene Foundrymen (also called the Shipbuilders in some reports) who won silver in the 1934 Ontario Baseball Amateur Association championship.

His friends encouraged him to attend a tryout game for the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International Baseball League, a farm system for the major leagues. At the tryout, Marchildon struck out the side in two straight innings and got an immediate offer to pitch in the big city.

The legendary baseball manager Connie Mack watched Marchildon develop in Toronto for a season and called him up to his Philadelphia Athletics team in 1940. His first two rookie outings were disastrous but with a fastball in the 90s and a lively curve ball, the A’s knew he just needed some experience. He went 10-15 in 1941, and he was on his way.

Phil Marchildon

The next season the A’s only won 55 games, and Marchildon got the W in 17 of them. He was on his way to being a star player, but Marchildon could not sit idly by when the war was underway and every healthy man was hearing the call for duty. He enlisted in the RCAF. He was trained throughout 1943 and was assigned to his first mission in 1944 as part of a seven-man crew. He was given the position of tail gunner, a position not all that different from being a pitcher. You were all alone, your back to your teammates, the enemy was coming for you first, and it was your job to mow ‘em down with the best shots you could target at them. Being in the spotlight out on the pitcher’s mound was fraught with pressure, but being in the crosshairs as a tail gunner was fraught with peril.

He flew 26 missions. On the last one, all the fears came to pass. Their plane caught fire over northern Germany. Crewmembers had to abandon the bomber. The tail gunner is in a particularly precarious position in such aircraft. They are frequently the first ones targeted by enemy air attack, and if there is any airborne emergency, the tail gunner has to crawl through the tail tube to even consider escape. Somehow Marchildon and one other soldier aboard, George Gill, managed to parachute out of their disabled Halifax. They plunged into the cold, salty waves near Denmark, where four hours later Danish fishers heard their cries.

Denmark was not allied with Germany, but Hitler’s establishment considered that country a de facto brother state. The Nazis limited the brutality of their Danish occupation. When the Danes pulled the two Canadians from the water, that was as close to rescue as they would come. Nazis were waiting to collect them on shore.

Marchildon was officially “Missing In Action” while he was imprisoned in the infamous Stalag Luft III prison camp (the setting of post-war movies The Great Escape and The Wooden Horse). For nine months he barely survived malnutrition and other desperate conditions as the war waged. In the final days, he and the other allied inmates were subjected to a death march as their captors forced them out into the winter elements to hike en mass to other POW camps to avoid advancing Soviet troops. They were finally liberated by Allied soldiers only days before the final end of the war.

Marchildon, with an emaciated body and a traumatized mind, was sent home into the waiting embrace of his fiancé Irene. Together, they faced the emotionally crushing aftermath of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Marchildon as an airman in the RCAF. Photo: Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame

The POW camp was liberated in April. Connie Mack was soon contacting him to come pitch for the A’s and on August 29 at Shibe Park he was re-introduced to the fans who treated him to Phil Marchildon Night with ceremonies in between that night’s double-header. He then took the mound and pitched five innings of one-run ball in the second game.

That was just the beginning of his second act in baseball. In the 1946 season, he won 13 games for the lowly A’s, earned a 3.49 ERA and a WHIP of 1.372 – all while still trying to recover some of the 30 pounds he lost in the prison, joint and muscle deterioration, and somehow quiet the demons in his mind that sometimes came to visit him on the mound while tens of thousands of fans were screaming.

His 1947 results were even better. He was the Athletics’ opening day pitcher, got 19 wins on a losing ball club, two shutouts, and a 3.22 ERA that year. He faced a career high 1,172 batters for the season, 21 of his starts were complete games, and threw but one wild pitch the entire year. However, he led the majors in walks issued (140) and batters hit by pitches (seven) and at the age of 33, the signs of twilight were starting to glow on the horizon of his career.

It was an impressive career by any estimation. He pitched to future Hall of Famers like Yogi Berra, Ted Williams, George Kell, Joe DiMaggio, Bobby Doerr, Luke Appling, Jimmie Foxx and Joe Cronin.

The next season was notable for another reason. Jackie Robinson may have broken the colour barrier first, but 1947 also saw four others make the jump from the Negro Leagues. Robinson and his fellow Brooklyn Dodger teammate Dan Bankhead played in the National League, so Marchildon never got to face them. However, Marchildon lined up against three of the five that year – the American League colour pioneer Larry Doby of Cleveland, Willard Brown of the St. Louis Browns (both went on to the Hall of Fame), and Hank Thompson also on the Browns.

In the 1948 season, in a July 15 doubleheader with Cleveland, Marchildon pitched game one and the first black pitcher in the American League (Bankhead broke the National League colour barrier for pitchers with Brooklyn the season before), Satchel Paige, pitched in game two. Paige made his majors debut less than a week earlier on his way to the Hall of Fame.

Marchildon also went head to head with future Hall of Fame pitchers like Hal Newhouser and Bob Feller.

Feller was another who interrupted his stellar career to go to war, as did Marchildon’s Athletics teammate Dick Fowler who was also away for three years before returning to the Philadelphia starting rotation. Fowler was inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame two years after Marchildon – two Ontario boys in the A’s rotation at the same time.

The war and the baseball would be inextricable for Marchildon, no matter what the on-field results. He would later say that the war heaped upon him all the worst circumstances his life would encounter and yet he did not regret his service to country and taking on the battle for democratic freedom.

His wife Irene was another element to the Marchildon story. She bore the private weight of his PTSD right alongside him, even if such things were not understood in those times. She and Marchildon carried on together when, in hindsight (again, not a well understood condition at the time), Marchildon tore a rotator cuff but continued to pitch. This amplified the loss in his effectiveness in his last years in baseball. Irene would stand by his side as a true life-partner through it all. Wolf called it “a beautiful love story” underpinning the battles on the ball fields and in the air.

He struggled in 1950 in Triple-A Buffalo, he tried out for the Maple Leafs again in 1951 but couldn’t make the team, and sank into a brief depression over his forced retirement from baseball while still a relatively young man.

Photo: Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame

Once again, though, his fortunes made a strong defensive play. Marchildon got a job at an aviation company – one that was working on a little project he had some background with. It was a little air force project called the Avro Arrow, a prototype Canadian fighter jet that had the world excited. Despite the plane’s stellar training flight results, the development program got cancelled due to politics. Marchildon and the Arrow were together as military brothers, both noted for hurtling missiles with speed and precision, both forced to retire before their time for reasons they could not control or overcome.

“So many people have never heard of him, but he has such a compelling story,” said Wolf. “The family has said for years ‘Phil’s story has got to be a film, his life was just mind-blowing’ and my brother Luke is the catalyst of this.”

Wolf feels ready to take it on now thanks in large part to the storytelling and baseball atmosphere she experienced behind the scenes in The Silent Natural. It was an American story, shot mostly in Kentucky, with an almost entirely American cast and crew (notable fact: all deaf characters in the film were portrayed by deaf actors), but Wolf felt strongly moved by the Dummy Hoy narrative.

She met the movie’s director and lead scriptwriter Dave Risotto at the AFM (American Film Market) Convention several years ago and they struck up a working friendship. Wolf was transitioning into the film industry after many years primarily in the music sector, and Risotto had been involved in a number of past endeavours (eight years in the US Air Force including service in Vietnam, acting, film editing and more) leading him towards directing movies. “He needed a producer on board, and I really loved the story,” said Wolf. “We got along really well and shared a lot of the same ideas for getting the project from A to B to C.”

They linked up on the production team along with Branscombe Richmond (110 episodes of Renegade, among other credits) to assemble all the parts for The Silent Natural.

“It has been doing really well. It was such a cool process, really fun, and the Dummy Hoy story is pretty cool: the first deaf Major League Baseball star,” said Wolf. “It looks great, it has some great people in it, great actors, a lot of people really like it, it won a bunch of awards in film festivals. It’s still out there doing cool, incredible things.”

Risotto insisted that she have a small on-screen part in the film. The only other Canuck in the cast was Canadian film legend Tyler Mane (Sabretooth in the X-Men franchise, Chopper in the TV series of the same name, iconic horror character Michael Myers in the Halloween reboot). The movie tough-guy from Saskatchewan played the part of a protective teammate who sticks up for Hoy when others on the team were hostile to the deaf player in their midst.

“Tyler and I went to a guitar show when we were in Nashville,” said Wolf (Nashville was near their filming location). “It was pretty funny, actually. I ended up buying this mandolin / banjo thing that I haven’t played since I bought it, pretty much, it’s this insane thing. And he bought a really cool acoustic guitar. He’s an amazing guitar player, actually. So yeah, the two Canadians on the production, that’s it, just the two of us.”

In the way a Canadian can feel moved by an American tale, she knows the Marchildon story will be embraced by Americans and the world. An interesting life transcends all borders.

“It’s true Canadian history and I feel so strongly that this story be told,” she said.

The major challenge she faces is accumulating the funding to roll cameras. She’s making pitches of her own, now, everywhere from board rooms to elevators where investors might be. But like Marchildon’s fastball, she is confident this film will strike financial success. It’s a Canadian project with appeal in the United States, England, and beyond.

“It’s my blood. I was literally born to do this. The family has been waiting for some film director to take this on, and it was perfect that it be me. I’ve got one baseball film under my belt, and it’s a really cool period piece, a story about the underdog, and I think this one is just like that, beautiful stuff in it all over the place, and it’s my family.”

|

NorthPaws get a timely hit in the seventh to complete the comaback against the AppleSox

NightOwls Wings Get Clipped In An Exhibition Game Against The Nanaimo Selects

Victoria HarbourCats – Dudes hold on for narrow win on Fireworks night

Newsletter

Trending

-

Summer Collegiate2 weeks ago

Summer Collegiate2 weeks agoVictoria HarbourCats – Cats complete comeback with walk-off win

-

Summer Collegiate2 weeks ago

Sweets leave a sour taste taking the series finalie in Walla Walla

-

Summer Collegiate2 weeks ago

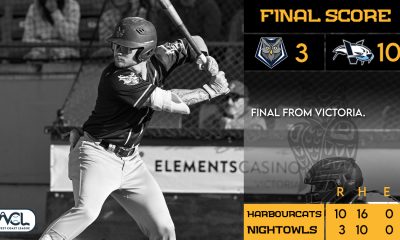

Summer Collegiate2 weeks agoVictoria HarbourCats – Cats shutout Owls in series opener

-

Summer Collegiate2 weeks ago

Summer Collegiate2 weeks agoVictoria HarbourCats – Cats sweep Owls with huge win

-

Summer Collegiate2 weeks ago

Seven strong innings from Chien help NorthPaws win series opener

-

Summer Collegiate1 week ago

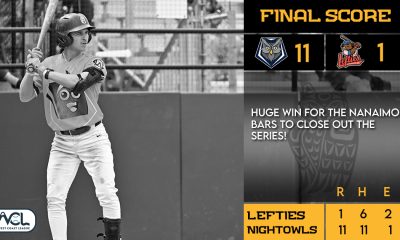

Summer Collegiate1 week agoHuge Win For The Nanaimo Bars To Close Out The Series

-

Summer Collegiate2 weeks ago

Summer Collegiate2 weeks agoSeries Finale In The Harbour City Sees The NightOwls Leave Empty-Handed

-

Summer Collegiate2 weeks ago

Summer Collegiate2 weeks agoVictoria HarbourCats – CCBC Golden Tide announce Vlaj as Head Coach, fill out coaching staff

You must be logged in to post a comment Login